Wabi-sabi.

It’s a concept, an aesthetic, and a worldview. It’s also a phrase that doesn’t translate directly from Japanese into English, and the ideas behind it may not immediately translate in the minds of those who haven’t encountered it before. Put simply, it’s an intuitive way of living that emphasizes finding beauty in imperfection, and accepting the natural cycle of growth and decay. The best way to learn about wabi-sabi is just to accept that it’s there – and to begin noticing examples of it in one’s daily life.

The words wabi and sabi were not always linked, and they can still be used separately in the Japanese language. Wabi, stemming from the root “wa,” which refers to harmony and tranquility, has evolved in meaning from describing something sad and desolate to describing something that is purposely humble and in tune with nature. A wabibito – literally, a “wabi person” – can do more with less, and is content with a life lived free of material possessions. Think Henry David Thoreau, or, more recently, “Cadillac Man,” who wrote recently in the New York Times about the simple joys and freedoms of his many years spent homeless in several of New York’s boroughs.

Sabi by itself refers to the natural progression of time, and carries with it an understanding that all things will grow old and become less conventionally beautiful. However, things described as “sabi” carry their age with dignity and grace. At the heart of being sabi is the idea of authenticity. I’m reminded of the classic children’s story, The Velveteen Rabbit, in which only the oldest, shabbiest, and most well-loved toys in a child’s collection magically become “real.”

In the summer of 2004, a Tokyo housewife named Shoko paid me to sit with her two afternoons a week and help her practice English pronunciation. She supplied coffee, a digital voice recorder, and two copies of a little book about the traditional Japanese tea ceremony. I supplied endless lessons about how the tongue hits the teeth when forming the “th” sound. We read the book out loud together. We said “thin tea” over and over. The city shrieked below us, and occasionally our lessons were cut short by political dissidents who assembled with microphones and loudspeakers in the courtyard outside the classroom building. Shoko’s pronunciation improved over the summer, though in general conversation she still couldn’t hit that “th” quite right. I was okay with this. Those very odd, very wabi-sabi lessons are some of my favorite memories of working in Japan.

The tea ceremony itself is an example of how wabi-sabi manifests itself in Japanese culture. While developed by Zen masters and monks, it was adopted in the fourteenth century by wealthy noblemen who built elaborate tearooms and served tea with expensive utensils imported from China. In the sixteenth century, however, the tea master Sen no Rikyu introduced a version of the ceremony that could be performed in small tea huts, with utensils made by indigenous craftsmen. The non-wealthy masses embraced Rikyu’s tea ceremony, which became known as wabichado (with chado meaning “the way of tea”).

The ceremony today can be understood and practiced by Zen monks, wealthy tea-masters, and Tokyo housewives alike (and possibly even their pronunciation teachers). Guests at the ceremony would be rightfully taken aback if the host’s home was unclean in any way, or if the traditional procedure of the ceremony was not followed correctly. However, if tea is served in imperfect heirloom cups, or with inexpensive – albeit beautiful – utensils, the guests should feel no affront.

Some culture-watchers predict that wabi-sabi will follow feng shui as the next Eastern concept that’s adopted by Westerners — and in turn by Western commercialization. This, however, seems unlikely, as the very idea of wabi-sabi requires us to get away from material objects as much as possible. Retailers wanting to capitalize on feng shui could market those little tabletop electronic fountains without betraying the definition of the idea. What sort of wabi-sabi-themed product could possibly be taken semi-seriously at your local housewares retailer? A lovely ceramic bowl with a deliberate crack? An embroidered silk pillow with part of the pattern left unfinished? Probably best not to give anyone ideas.

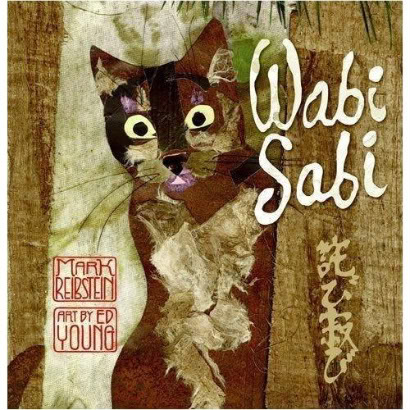

One welcome example of wabi-sabi entering the consumer marketplace happened in 2008, when the publisher Little, Brown released a new picture book called Wabi Sabi. In it, author Mark Reibstein and illustrator Ed Young explore the idea in a way that pieces together a definition of the concept through narrative, poetry, and collage artwork. The story involves a young cat named Wabi Sabi who journeys across her hometown of Kyoto, Japan in search of insights into the meaning of her name. The various animals she encounters in her trek present her with figurative examples of simple, imperfect, and unexpected beauty, sometimes in haiku.

Elizabeth Bird, children’s librarian at the New York Public Libraries, wrote a great review of the book upon its release last October. She explained the use of haiku and the overall mood of the book:

“What Wabi Sabi does is to place these haikus within the context of a larger tale. When that happens, the little sayings and moments are set apart. They are shots of quietude in the midst of a busy narrative. As a result, the entire book has a kind of calming effect on the reader.”

Bird, a prolific reviewer of children’s literature, expressed frustration at how she had described the book to prospective readers (“It is not an easy book to describe. I keep trying to give you some vast sense of the whole, and instead I keep finding myself returning to descriptions of single moments”). A commenter noted that perhaps Bird’s review was itself an example of wabi-sabi, in that its imperfections endeared readers to the book even more.